|

|

|

What

is a contrafactum?

definition

[The absence of contrast between

'secular' and 'sacred' styles of music in the Middle Ages] 'can be shown simply by the

observation that a secular song, if given a set of sacred words, could serve as sacred

music, and vice versa. Only recently has it been recognized how frequently such

interchange took place, and the more we learn about medieval music, the more important it

becomes. The practice of borrowing a song from one sphere and making it suitable

for use in the other by the substitution of words is known as "parody" or contrafactum.' [The absence of contrast between

'secular' and 'sacred' styles of music in the Middle Ages] 'can be shown simply by the

observation that a secular song, if given a set of sacred words, could serve as sacred

music, and vice versa. Only recently has it been recognized how frequently such

interchange took place, and the more we learn about medieval music, the more important it

becomes. The practice of borrowing a song from one sphere and making it suitable

for use in the other by the substitution of words is known as "parody" or contrafactum.'

(Manfred F.

Bukofzer, 'Popular and Secular Music in

England', in The New Oxford History of Music 3: Ars Nova and the Renaissance,

1300-1540, ed. Anselm Hughes and Gerald Abraham (London: Oxford University Press,

1960), p. 108.)

the functions of the contrafactumThe

contrafactum (plural contrafacta) may operate in either direction: to

provide pious words to fit a secular song, or profane words to fit a religious song. It

may involve 'parody' in the literary sense, offering purposeful variations on the words of

the original song, but sometimes there may be only a more general contrast in content

between the two songs, or even no obvious relationship at all between them. Although in

some cases it is possible to tell which came first, the religious or the secular version,

in others it is less clear in which direction the process operated.

sacred to secular

Examples of this can be found particularly in Goliardic verse, which sometimes parodies

the forms of hymns and the church services; for instance, the first line of the

sixth-century Latin hymn for Prime, Iam lucis orto sidere, which

celebrates control of both the emotions and the appetites (potus cibique parcitas, 'restraint in food and drink'), is borrowed to introduce a twelfth-century drinking song:

|

Iam lucis orto sidere

Deum precamur supplices

ut in diurnis actibus

Nos servet a nocentibus . . . |

Now at the dawning

of the day

To God as suppliants we pray

That from our daily round he may

All harmful beings keep away . . . |

| becomes: |

|

Iam lucis orto sidere

statim oportet bibere;

Bibamus nunc egregie

Et rebibamus hodie . . . |

Now at the dawning

of the day

We must start drinking straight away;

Let's drink now till the drink's all gone,

And have another later on . . . |

|

(Texts from

F.J.E. Raby, ed., The Oxford Book of

Medieval Latin Verse (Oxford: Clarendon, 1959), nos. 41 (p. 53) and 237 (pp. 362-3);

my translations).

secular to sacred

This kind of contrafactum becomes commoner in the later Middle Ages; it is

particularly associated, from the early thirteenth century onwards, with the work of the

friars, who often supplied pious words to be sung to popular secular tunes (a device later

to be taken over, for similar reasons, by the Salvation Army, on the principle 'Why should

the Devil have all the best tunes?'). St Francis described his followers as joculatores

Dei, 'God's minstrels'. An example of this can be found in the Red Book of Ossory

(Bishop's Palace, Kilkenny), which includes 60 Latin lyrics in two hands of the late C14,

accompanied by a note:

Attende, lector, qu[o]d

Episcopus Ossoriensis fecit istas cantilenas pro vicariis Ecclesie Cathedralis

sacerdotibus et clericis suis ad cantandum in magnis festis et solaciis, ne guttura eorum

et ora Deo sanctificata polluantur cantilenis teatralibus, turpibus et

secularibus, et cum

sint cantatores prouideant sibi de notis conuenientibus secundum quod dictamina

requirunt.

Be advised, reader, that the Bishop

of Ossory [the Franciscan friar Richard de Ledrede, d. 1360] has made these songs for the

vicars of the cathedral church, for the priests, and for the clerks, to be sung on the

important holidays and at celebrations in order that their throats and mouths, consecrated

to God, may not be polluted by songs which are lewd, secular, and associated with revelry,

and, since they are trained singers, let them provide themselves with suitable tunes

according to what these sets of words require.

(Text and translation from Richard

Leighton Greene, ed., The Lyrics of the Red Book of Ossory, Medium Aevum

Monographs n.s. 5 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1974), pp. iii-iv.)

25 of the Latin lyrics

are on the Nativity or related themes, 11 on Easter and the Resurrection, one on the

Annunciation, the rest on various devotional topics. Some of them are accompanied by

introductory fragments of English or French verse, whose form (though not content) they

seem to echo: e.g. the first line of the popular dance-song 'Maiden on the moor' ('A

maiden stayed on the moor for a full week and a day . . .') prefaces a lyric on the

Nativity:

|

Maiden in the

mor lay,

in the mor lay,

seuenyst[es] fulle,

seuenist[es] fulle.

Maiden in the mor lay--

in the mor lay--

seuenistes fulle,

[seuenistes fulle,

fulle] ant a day... |

Peperit

virgo,

Virgo regia,

Mater orphanorum,

Mater orphanorum,

Peperit virgo,

Virgo regia,

Mater orphanorum,

mater orphanorum,

Plena gracia... |

A virgin gave birth,

A royal virgin,

Mother of orphans,

Mother of orphans,

A virgin gave birth,

A royal virgin,

Mother of orphans,

Mother of orphans,

Full of grace... |

| (ME text

(from Oxford, Bodleian Library, Rawlinson MS D. 913; slightly modified here) and Latin

text from Greene, ed., The Lyrics of the Red Book of Ossory, p. x). |

doubtful cases doubtful cases

In some cases, paired lyrics of this kind survive

without any clear evidence of precedence.

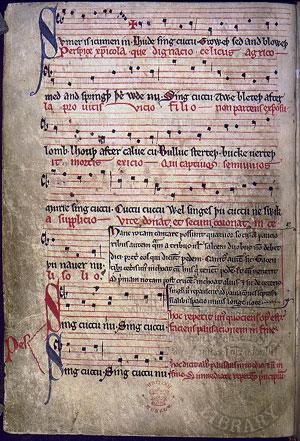

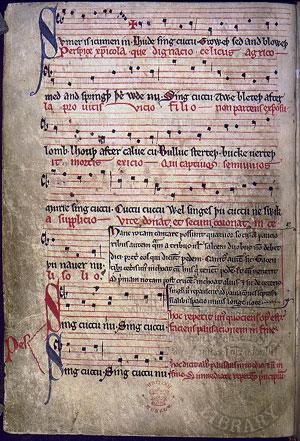

One example of this is Sumer is icumen

in, in London, British Library, Harley MS 978, where a single piece of music is

accompanied by both a vernacular and a Latin text (see illustration; click on title

for full edition): which came first, the Latin Easter hymn (in red ink) or the frivolous

English spring song (in black)?

Another is the two lyrics Lvtel wot

hit any mon / Hou loue hym haueth ybounde and Lutel wot hit any mon / Hou derne loue

may stonde, paired by the scribe in London, British Library, Harley MS 2253

(click on titles for full edition).

In cases like this, the relationship between the two poems has to be conjectured on their

internal evidence. |

|

[The absence of contrast between

'secular' and 'sacred' styles of music in the Middle Ages] 'can be shown simply by the

observation that a secular song, if given a set of sacred words, could serve as sacred

music, and vice versa. Only recently has it been recognized how frequently such

interchange took place, and the more we learn about medieval music, the more important it

becomes. The practice of borrowing a song from one sphere and making it suitable

for use in the other by the substitution of words is known as "parody" or contrafactum.'

[The absence of contrast between

'secular' and 'sacred' styles of music in the Middle Ages] 'can be shown simply by the

observation that a secular song, if given a set of sacred words, could serve as sacred

music, and vice versa. Only recently has it been recognized how frequently such

interchange took place, and the more we learn about medieval music, the more important it

becomes. The practice of borrowing a song from one sphere and making it suitable

for use in the other by the substitution of words is known as "parody" or contrafactum.' doubtful cases

doubtful cases