|

What

is mouvance?

introduction

Editors working on

the vernacular literatures of the Middle Ages may be faced with very

different problems from the editors of classical works. Editors working on

the vernacular literatures of the Middle Ages may be faced with very

different problems from the editors of classical works.

Traditionally, the

task of the editor of classical works has been seen as the examination

and (where possible) comparison of surviving manuscripts to identify and

eliminate those features of their texts which are scribal rather than

authorial, in order to 'reverse the process of transmission and restore

the words of the ancients as closely as possible to their original form'

(Reynolds

and Wilson (1974), p. 212).

For some medieval

vernacular works, this approach is arguably appropriate. There is no

doubt, for instance, that Chaucer in the late fourteenth century saw the

verbal integrity of his work as important, and felt that it was

threatened by the process of scribal transmission. Taking leave of his

work ('Go, litel bok') at the end of Troilus and Criseyde, he

hopes that the lack of standardization in the spoken and written English

of his time will not erode its poetic quality in the course of

transmission ---

And for ther is so gret diversite

In Englissh and in writyng of oure tonge,

So prey I God that non myswrite the,

Ne the mysmetre for defaute of tonge ...

( Troilus and Criseyde, 5. 1793-6, ed. Benson

(1988), p. 584)

--- and elsewhere he wishes a scalp infection on Adam, his personal

scribe, if he doesn't improve the accuracy of his copying in future:

Adam scriveyn, if ever it thee bifalle

Boece [Boethius] or Troylus for to writen newe,

Under thy long lokkes thou most have the scalle

But [unless] after my makyng [composition] thow write more trewe.

So ofte aday I mot thy werk renewe,

It to correcte and eke to rubbe and scrape,

And al is thorugh thy negligence and rape [haste].

(Chaucers wordes unto Adam, his owne scriveyn, ed. Benson

(1988), p. 650).

However, the textual

transmission of some other medieval vernacular works suggests less

concern for the textual integrity of the original work, and a less

clearly-marked distinction between the functions of author and scribe. Cerquiglini

(1989), p. 57, has argued that 'L'oeuvre

littéraire, au Moyen Age, est une variable ... Qu'une main fut

première, parfois, sans doute, importe moins que cette incessante

récriture d'une oeuvre qui appartient à celui qui, de nouveau, la

dispose et lui donne forme' ('The

literary work, in the Middle Ages, is a variable ... The fact that one

hand was the first is sometimes, undoubtedly, less significant than

this constant rewriting of a work which belongs to whoever recasts it

and gives it a new form').

top

Zumthor's

concept of

mouvance

The concept of mouvance

was formulated by Paul Zumthor in the second chapter of his study of medieval French poetry, Essai de poétique

médiévale (Zumthor,

1972). Zumthor noted the contrast between the relatively fixed texts

found in manuscripts of the works of some named late-medieval French

poets (Charles d'Orléans, Guillaume de Machaut) and the much more

common medieval combination of authorial anonymity (or near-anonymity)

and a high level of textual variation, which might involve not only

modifications of dialect and wording but more substantial rewriting and the

loss, replacement, or rearrangement of whole sections of a work.

He used the term mouvance to describe this textual mobility.

Zumthor argued that

anonymity and textual variation were connected: medieval vernacular

works were not normally regarded as the intellectual property of a

single, named author, and might be indefinitely reworked by others,

passing through a series of different 'états du texte' ('textual

states')

(p. 72). The modern emphasis on 'textual authenticity' (i.e. the attempt

to reconstruct the author's original as the only authentic version of

the text) was therefore anachronistic as an editorial approach, ignoring

the 'mobilité essentielle du texte médiéval' ('the essential mobility

of the medieval text', p. 71). To avoid this anachronism, our concept of

the medieval 'work' (oeuvre) needed to be redefined.

Diagram:

'work' and

'text'

(based on the diagram

in Zumthor

(1972), p. 73)

Zumthor emphasised

that the term 'work' (oeuvre) in this diagram should not be

identified with the archetype in the traditional editorial diagram of manuscript

relationships, the stemma. It represented not the historical

antecedent of the surviving manuscripts, but 'l'unité complexe ... que

constitue la collectivité des

versions en manifestant la matérialité; la synthèse des signes

employés par les "auteurs" successifs (chanteurs, récitants,

copistes) et de la litteralité des textes ... L'oeuvre est

fondamentalement mouvante' (p. 73) ( 'the complex unity

constituted by the collectivity of its material versions;

the synthesis of the signs employed by the successive

"authors" (singers, reciters, copyists) and of the literality

of the texts .... The work is fundamentally mobile'). The 'work' was not

static, a chronological starting-point for the process of manuscript

transmission, but dynamic, passing in the course of its transmission

through phases of growth, transformation, and decline.

Zumthor explained mouvance

as a product of the oral

culture of the Middle Ages, an 'intervocal' (as opposed to 'intertextual')

network offering access to a variety of possible resources for poetic

composition; the different realizations of a 'work' reflected a

continuing interaction between written and oral culture at each stage of

transmission (see the section on 'Intervocalité et mouvance' in La

lettre et la voix (Zumthor

(1987)), pp. 160-8).

top

later

developments

Some more recent

textual theorists have explored similar issues, questioning the textual

'authority' of the medieval vernacular author and, more generally,

examining the ways in which the creation of a 'work' might be seen as a

communal process extending over time rather than than an individual act

of literary production.

Jerome J.

McGann, for

instance, argued in A Critique of Modern Textual Criticism (McGann

(1983)) that even modern literary works 'are fundamentally social

rather than personal or psychological products' (p. 43). 'The fully

authoritative text is . . . always one which has been socially produced;

as a result, the critical standard for what constitutes

authoritativeness cannot rest with the author and his intentions alone'

(p. 75). The role of printers, editors, even friends, in the production

of successive stages of a literary work needs to be taken into account;

and the printed version of an author's draft may offer opportunities not

only for contamination but for decontamination ('Authors' works are are

typically clearer and more accessible when they appear in print', p.

41).

Two books, one

French, one English, can be used to illustrate approaches to the

specific problems of editing medieval works ...

top

Cerquiglini,

Éloge de

la variante

(1989)

Bernard

Cerquiglini,

in his brief, witty, and incisive 'critical history of philology', Éloge de

la variante (Cerquiglini

(1989)), offers a post-structuralist sequel to Zumthor's work. He

avoids Zumthor's 'beau terme de mouvance' because of its

association in Zumthor's work with oral culture, preferring the term variance

(p. 120, n. 19). His emphasis is less on the relationship between oral

and written than on the relationship between the varying written

realizations of medieval vernacular works, and the implication of their

variance for the medieval concept of textual authority. Like Zumthor, he

sees this purposeful variation (the scribe's 'intervention consciente',

p. 79) as intrinsic to the transmission of medieval Romance works.

Cerquiglini argues that it is anachronistic to see works of this

kind as the intellectual property of a single author, textually fixed at

the 'moment unique où la voix de l'auteur, que l'on suppose, se noua à

la main du premier scribe, dictant la version authentique, première et

originelle' (p. 58) ('[the] unique moment when the imagined voice of the

author linked itself with the hand of the first scribe, dictating the

first, authentic, and original version' ). In taking all manuscript

variants as errors, the editors of medieval vernacular works have

misunderstood their essential nature: 'Dans l'authenticité

généralisée de l'oeuvre médiévale, la philologie n'a vu qu'une

authenticité perdue' (p. 58) ('In the generalized authenticity of the

medieval work, philology has seen only a lost authenticity').

Cerquiglini also

questions (referring to the discussion of Kane and Donaldson's edition

of Piers Plowman in Patterson(1985);

see further Conclusions, below)

the assumption in much textual criticism of an 'auteur transcendant ...

[qui] tranche absolument, par l'unicité de sa conception,

l'opacité de son oeuvre (argument de la lectio difficilior), la

qualité de sa langue, avec la diversité scribale, ignorante et sans

dessein, qui pluralise l'oeuvre, en banalise l'expression, appauvrit la

langue' (pp. 90-1) (a transcendent author ... absolutely distinguished,

by the unity of his conception, the opacity of his work (argument of the

lectio difficilior [i.e.that the more difficult MS reading is

likely to be the original one]), the quality of his language, from the

scribal diversity, ignorant and unplanned, which pluralises the work,

makes its expression banal, impoverishes its language').

He argues that not

only traditional stemmatic editing but the 'best-text' method advocated

by Bédier

(1928), who preferred the conservative editing of a single MS text,

assimilates the medieval work 'au texte autorisé, stable et clos, de la

Modernité' ('to the authorised, stable and closed text of the modern

era'). Stemmatic editing offers an 'illusory reconstruction' of the

work, 'best-text' editing 'only snapshots' (p. 101); both marginalize

(literally as well as metaphorically) its actual variance, relegating

it, in selected and fragmented form, to the apparatus criticus at

the foot of the page. Parallel-text editions are an inadequate solution

to the problem; Cerquiglini sees information technology as the way

forward, since the interactive, multidimensional space of the electronic

edition can offer both more textual information than the printed edition

and easier comparison of different versions of a work. The production of

works electronically in itself mirrors medieval conditions of production

more accurately than print technology: 'L'écrit électronique, par sa

mobilité, reproduit l'oeuvre médiévale dans sa variance même' (p.

116) ('electronic writing, by its mobility, reproduces the medieval work

in its actual variance' ).

top

Machan,

Textual Criticism and Middle English Texts (1994)

A similar approach,

applied to the editing of Middle English rather than Old French works,

appears in Tim William Machan's Textual Criticism and Middle English

Texts (Machan,

(1994)).

Machan argues that

the editing of Middle English works has been dominated by a powerful

'Humanist' tradition of textual criticism, 'lexical' (seeing the work as

essentially a verbal construct), 'idealist' (giving the authorially-intended

work precedence over its specific documentary realizations), and

equating the authorial with the authoritative text. The manuscript

evidence, however, suggests that this approach is anachronistic. The

work is characteristically treated as 'a nonlexical, not self-contained res

inseparable from the supplements of others' (p. 165): its verba

(words, rhymes, etc.) are a less important feature than its res

(content), it may be modified or expanded during textual transmission,

and its documentary realizations in manuscripts of varying content and

layout further modify its meaning for the medieval reader. Textual

authority in this period was normally the prerogative of the Latin auctores,

and Machan argues that the evident anxiety of some late-medieval

vernacular authors (including Chaucer) about the integrity of their

texts suggests that they had not yet achieved this kind of authority

Machan suggests that

a genuinely historical edition of a medieval work might entail

reconstructing 'the work behind a document' rather than an 'authorized

text' underlying the surviving documents (p. 184), taking into account

the social and cultural framework within which it would have been read,

and giving greater attention than at present to the bibliographical

codes (e.g. page layout, choice of script, illumination) involved in its

documentary realization.

top

three illustrations

Zumthor applied his

concept of mouvance to specific types of medieval vernacular

work, more or less closely linked to oral traditions: the chansons de

geste, romances, lyric poetry, and the fabliaux. The fluidity

of form and content that he noticed in this kind of work can, however,

be found in other types of medieval literature (although not necessarily

for the same reasons). The illustrations below offer a few specific

Middle English examples: from popular romance (Sir Orfeo),

religious lyric (see case-study),

and works of spiritual instruction (Ancrene Wisse).

popular

romance:

Sir Orfeo

Most undergraduates

studying Middle English encounter this charming short romance in the

text preserved in the 'Auchinleck manuscript' (Edinburgh, Advocates'

Library, MS 19. 2. 1), probably produced in London c. 1330.

It tells the story of

a harper-king, Orfeo, whose wife Heurodis is carried off by the king of

the fairies. He leaves his kingdom in charge of a steward and goes into

the wilderness to mourn her loss. After more than ten years of solitary

hardship, he sees her riding through the wilderness with a troop of

ladies; he follows her through a tunnel in the rock into a beautiful

country with a castle built of gold and precious stones. He gains entry

to the castle as a harper; there he finds people abducted by the

fairies, who were 'thought dead, and are not'. He wins back his wife

from the king of the fairies through his skill in harping, and returns

to his court still dressed as a travelling minstrel; his steward does

not recognize him, but welcomes him nevertheless for the king's sake.

Orfeo then reveals his identity and resumes the throne; the faithful

steward, overjoyed by his return, eventually succeeds him as king.

The Auchinleck

version of this story, however, represents only a single stage in a

sequence of narratives extending from classical times to the late

nineteenth century, crossing geographical, cultural, linguistic,

generic, and stylistic boundaries, and transmitted both orally and in

writing. The earlier history of this sequence raises the question of

authorship: how far can the anonymous poet who first put the story into

Middle English verse be described as its 'author' in the modern sense?

Its later history raises the question of authority: how far was the

original Middle English version regarded as 'authoritative'?

As the names of the

characters suggest, one source of the Middle English romance was the

classical legend of Orpheus and Eurydice. Before the narrative was

turned into Middle English, however, it had already merged with legends

of the Celtic underworld, probably in Brittany (see Walter Map's

late twelfth-century miscellany, De Nugis Curialium (ed. James

(1983)), Dist. 2, ch. 13, and Dist. 4, Ch. 8, for a similar

story of fairy abduction, set in Brittany). There are references in

French romances of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries to a Breton lai

of Orpheus; and the Middle English version is introduced, in two of the

three manuscripts, by a prologue (lost in Auchinleck) linking it to the

Breton lais. Internal evidence suggests that the Middle English

version had as its immediate source an Old French narrative lai

(now lost) in octosyllabic couplets. In other words, the Middle English

version acknowledges its debt to earlier narrative, and probably owed

much to the content and style of its French original (with the possible

exception of the narrative motif of the faithful steward); should

it be seen as an original work, a translation, or something between the

two?

The Auchinleck MS is

the earliest of three MSS containing the Middle English version; London,

British Library, MS Harley 3810, dates from the early fifteenth century,

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 61, from the late fifteenth

century. There are considerable divergences between the three texts, too

numerous even to allow an edition in parallel columns (the standard

edition, Bliss

(1966), simply prints all three separately); in particular, the

Ashmole 61 text has numerous omissions, particularly towards the end,

probably the result of oral transmission. Even the Auchinleck MS does

not necessarily reflect the earliest ME version exactly; its confident

identification of Orpheus's original home, Thrace, with the ancient

capital of England,

For Winchester was cleped tho

Traciens, withouten no

(49-50)

('For Winchester was then called Thrace, without a doubt')

is not shared by either of the later

manuscripts.

A

later version of the story still is printed by Bliss

(1966), pp. l-li, the ballad of King Orfeo partially

transcribed in Unst, Shetland, in the later nineteenth century: the king

here is nameless, his wife is called Lady Isabel, and he wins her back

by his skill on the bagpipes.

The surviving English versions of the story reflect, particularly in their

reproduction of names, the degenerative process of 'Chinese whispers'

which is an inherent risk of both written and oral transmission: Orfeo

is said in the Auchinleck MS to be descended from 'King Pluto' and 'King

Juno', in Harley 3810 from 'Sir Pilato' and 'Yno', and 'Dame Heurodis'

in Auchinleck becomes 'Dame Meroudys' in Ashmole 61. But the textual

variants are not entirely the product of scribal error; sometimes they

reflect the more extensive textual modification caused by oral

transmission (for a detailed study of the

combination of memorization and recomposition reflected in some MSS of

ME romances, see Baugh

(1959)), sometimes purposeful adaptation for a different audience.

top

Medieval

religious lyric

Douglas Gray says of

the Middle English devotional lyric, 'It was not in its own time a

remote "aesthetic" literary form, but was an integral part of

the religious life of contemporary society ... more often than not the

impulse behind [the lyrics] is quite functional and practical' (Gray

(1972), p. 37). Douglas Gray says of

the Middle English devotional lyric, 'It was not in its own time a

remote "aesthetic" literary form, but was an integral part of

the religious life of contemporary society ... more often than not the

impulse behind [the lyrics] is quite functional and practical' (Gray

(1972), p. 37).

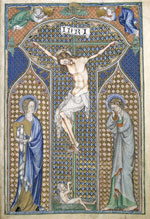

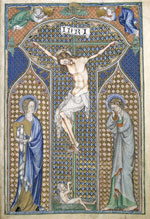

The case-study

provides six different texts of a meditation on the Passion linked to the visual image of the

Crucifixion; an echo of the same work can be seen in a stanza of the longer

Passion lyric in London, British Library, MS Harley 2253, I

syke when Y singe, lines 41-50. Although clearly related,

these short texts show a striking degree of variation in content,

wording, and even length.

Although some medieval English

devotional lyrics have named authors, this meditation is anonymous; its

content is highly conventional, and the first-person speaker who appears

in four of the six texts is less an authorial voice than a meditative persona

for the poem's users. While the overall structure of the argument,

and much of the poetic form, are retained in the individual versions,

the high level of variation (whether caused by purposeful recasting for

aesthetic or other reasons, memorial recomposition, or the

rationalization of manuscript problems) suggests that the users and transmitters of

the poem did not see its textual integrity as important.

top

Works

of spiritual instruction: Ancrene Wisse

The two previous

examples could be seen as illustrating specifically Zumthor's concept of mouvance:

both involve works which, although they survive to us in written form,

reflect the continuing influence of oral culture in their textual

development.

There may be other

causes, however, for textual mobility in medieval works. The

early-thirteenth-century Middle English guide for anchoresses, Ancrene

Wisse, survives in a number of manuscript versions which sometimes

differ very considerably from each other. The work was paraphrased,

modernized, and translated into French (twice) and Latin; it was

revised---both by its original author and by others---and adapted for

different audiences; and its content was selected, rearranged, and

incorporated into other devotional works.

The context of Ancrene

Wisse is written rather than oral (see Millett

(1993)); although its author is anonymous, the authorial 'I' of the

earliest versions seems to be a personal rather than an institutional

'I'; and some at least of its scribes seem to have taken considerable

care to reproduce its text accurately (the late-fourteenth-century

version in the 'Vernon manuscript' (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Eng.

poet. A. 1) is one of the most reliable manuscript witnesses).

The key to its

textual variation lies rather in its practical function as a work of

spiritual instruction; although it may have been valued for its

rhetorical skill, it was nevertheless pragmatically adapted, both by the

author and by some of his successors, for changing audiences and

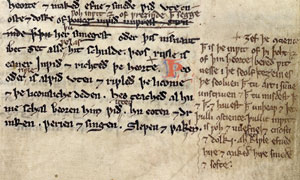

changing purposes. This illustration of

an early manuscript, London, British Library, Cotton Cleopatra C. vi,

shows corrections (probably by the author himself) to the Cleopatra

scribe's faulty text, but also his modifications (explanations and

revisions) to the original version; a rather later manuscript,

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 402, incorporates more extensive

revisions---again probably authorial---for a larger group of anchoresses

than the three addressed in the original version. This process of

revision and adaptation continued through the Middle Ages, as the work

was modified for the use of nuns, of male religious communities, and

even of the laity. The key to its

textual variation lies rather in its practical function as a work of

spiritual instruction; although it may have been valued for its

rhetorical skill, it was nevertheless pragmatically adapted, both by the

author and by some of his successors, for changing audiences and

changing purposes. This illustration of

an early manuscript, London, British Library, Cotton Cleopatra C. vi,

shows corrections (probably by the author himself) to the Cleopatra

scribe's faulty text, but also his modifications (explanations and

revisions) to the original version; a rather later manuscript,

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 402, incorporates more extensive

revisions---again probably authorial---for a larger group of anchoresses

than the three addressed in the original version. This process of

revision and adaptation continued through the Middle Ages, as the work

was modified for the use of nuns, of male religious communities, and

even of the laity.

The opposition in

'classical' textual criticism between author and scribe cannot be easily

mapped on to this kind of transmission. Although there is plenty of

evidence in the textual history of Ancrene Wisse (beginning with

the Cleopatra MS) for scribal 'negligence and rape', the transmission of

Ancrene Wisse seems to have taken place, particularly in the

early stages, in an institutional context where the functions of author

and scribe (as well as the intermediate functions of editor, reviser,

and corrector) were not always sharply differentiated; a possible model

for this context is offered by David d'Avray's study of the composition

and transmission of mid-thirteenth-century Paris sermons, Medieval

Marriage Sermons (d'Avray,

2001).

top

conclusions

The concepts of mouvance

and variance have been received --- where they have been received

at all --- with considerable suspicion by English textual critics; see, for

instance, Nicolas Jacobs' criticism of Machan's approach (Jacobs,

1998), which questions the historical accuracy of the claim that for

much of the Middle Ages there was no concept of 'authorship' for

vernacular works, and emphasises the distinction between 'creative

intelligence' and more low-level kinds of adaptation in the process of

textual transmission.

These objections

highlight two genuine problems. The first is the fondness of the

theorists of mouvance for sweeping, sometimes untenable,

generalizations; their approach may offer valuable insights into the

textual transmission of certain types of medieval work, but is it

really, either historically or methodologically, universally

applicable? The second is the question of textual quality: if

scribal rewritings (as Jacobs acidly remarks) are generally

characterized by 'dim-wittedness, literal-mindedness, and triviality'

(p. 5), is the editor obliged to renounce the concept of the

'transcendent author' and give them equal weight with authorial

readings? Might it not be intellectually more respectable, and

aesthetically more satisfying, to follow Kane and Donaldson's

approach to Piers Plowman (see Kane

and Donaldson (1975)), affirming the 'absolute difference' between

scribal and authorial readings, and the need to eliminate the former

from the edited text? Patterson elegantly (though not without irony) summarizes the Kane and Donaldson

approach: 'The scribes are many, the poet unique; the scribes write the

language of common men, the poet composes a language of his own. The

poet traces no conventional path but works out for himself the way of

genius, and it is the task of his editors to rediscover that way from

among the ruins of the manuscripts' (Patterson

(1985),

p. 97).

The two problems are

related: mouvance is more usefully seen as a significant aspect

of medieval vernacular literary transmission than as its defining

characteristic. The features which distinguish an oeuvre mouvante (authorial

anonymity, collective rewriting, influence from oral tradition, textual

changes for changing audiences or functions) are more likely to occur in

some types of medieval work than others; and the qualitative distinction

between an original 'authorial' input and that of later

contributors (scribes or others) to the textual transmission of a work

may similarly be more marked in some contexts than in others. The study of mouvance

is likely to be more rewarding (for instance) for an editor working

on

thirteenth-century Middle English lyrics than for one working on a major

late-medieval author.

The theory of mouvance,

however, has more general implications for the editors of medieval

vernacular works. Patterson, questioning Kane and Donaldson's exclusive

concentration on the reconstruction of the author's original,

nevertheless sees no alternative but the 'best-text' edition, which he

argues is an abdication of the editor's responsibilities, 'an edition

that, for all its conservative claims to soundness and reliability, in

fact represents an arbitrarily foreclosed act of historical

understanding' (Patterson

(1985),

p. 113). But the rehabilitation of the process of textual transmission

implied by the concepts of mouvance and variance offers

other possibilities.

Cerquiglini's 'multidimensional' approach

to editing proposes (as in the case-study

offered here) simultaneous access to all the MS evidence, with no single 'privileged' text. Cerquiglini's hope, however, that information technology would open up new possibilities for

'multidimensional editing' has not yet been fully realized. The 'years

of grinding labour' (in Peter Robinson's phrase) required for

multi-manuscript editions of even comparatively short works, and the difficulty of

obtaining continuing funding for large projects, remain a problem. Most

of the major electronic editions of medieval English works produced so

far have been (in Housman's words) editions in usum editorum 'for

the use of editors' --- manuscript facsimiles, transcriptions, and

electronic collations (see the section on Electronic

resources in the booklist), offering much fuller information on the

raw materials for the editorial process than was previously possible,

but not the user-friendliness or historical overview of a comprehensive edition.

But other types of

'multidimensional' editing are possible. D'Avray's recent study of Paris

marriage sermons (which might be significantly modified by different

preachers, or for different purposes, in the course of transmission)

offers a possible model (see d'Avray

(2001), pp. 43-45): d'Avray chooses a single manuscript version as a

representative of the textual tradition (not necessarily the earliest,

and 'not a "best manuscript", though it would be perverse not

to choose a good one', p. 40), and edits it in the light of the

tradition as a whole, correcting where necessary, and recording

significant textual variations and revisions in other MSS in the apparatus

criticus or (if extensive) in an appendix. The forthcoming

EETS edition of Ancrene Wisse will follow a similar approach (see

Millett

(1994)), using Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 402 not only as

a

relatively correct text incorporating some interesting revisions, but as

a

vantage-point from which the earlier and later development of the work

can be surveyed.

Postscript: for a more recent discussion of the issues involved

in editing 'Ancrene Wisse', see the EETS edition, in particular

the section on 'Editorial Aims and Principles' in the 'Textual

Introduction' to volume 1, pp. xlv-lxi:

Ancrene Wisse: A Corrected Edition of the Text in Cambridge,

Corpus Christi College, MS 402, with Variants from Other

Manuscripts, ed. by Bella Millett, drawing on the

uncompleted edition by E. J. Dobson, with a Glossary and

additional notes by Richard Dance, 2 vols., EETS 325, 326

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005, 2006).

home

| contents

| search | top

|

Editors working on

the vernacular literatures of the Middle Ages may be faced with very

different problems from the editors of classical works.

Editors working on

the vernacular literatures of the Middle Ages may be faced with very

different problems from the editors of classical works.

Douglas Gray says of

the Middle English devotional lyric, 'It was not in its own time a

remote "aesthetic" literary form, but was an integral part of

the religious life of contemporary society ... more often than not the

impulse behind [the lyrics] is quite functional and practical' (

Douglas Gray says of

the Middle English devotional lyric, 'It was not in its own time a

remote "aesthetic" literary form, but was an integral part of

the religious life of contemporary society ... more often than not the

impulse behind [the lyrics] is quite functional and practical' (